Druidess of Amherst: The Spiritual and Emotional Desires of Emily Dickinson

The Nineteenth Century was a brilliant time for American poetry. Some of the most famous works were penned during this period of enlightenment and exploration. One such poet was Emily Dickinson. Named the “Recluse of Amherst”, most of her poems were not discovered until after her death. Her writings explore her innermost desires and emotions, disappointment in love, her need to express herself, and most strikingly, her spiritual beliefs. Neither a member of traditional religious thought nor an outright skeptic, her poetry reveals a genuine and complex system of belief that was a result of the age in which she grew up, the atmosphere in which she was raised, and her own intense curiosity. Poetry is one of the purest manifestations of a person’s inner thoughts and desires. If this is true, then the images of spirituality and the afterlife painted by Dickinson in her many poems serves not to prove what she believed, but something far more interesting: what she wanted to believe.

If a student is asked about the poetry of Emily Dickinson, he or she will probably give an answer pertaining to her poetry about death and the process of dying. What he or she will not mention is the vast complexities of her emotions and desires that are expressed within the pines of her poetry. As someone who wrote for her own pleasure, not for profit, there is far less speculation about the authenticity of the feelings describes in her poems. In her works is painted a complex picture of what she desired to believe concerning spirituality as well as her own inner conflicts and emotions.

Emily Dickinson lived and wrote “in an age defined by the struggle to reconcile traditional Christian beliefs with newly emerging scientific concepts.” The new scientific theories and diverse religious movement at the time are undoubtedly reflected in in Dickinson and her works (Emily Dickinson and the Church). As a young girl, Dickinson was raised in a Calvinist home and attended church at The First Congregational Church of Amherst (Crumbley). The time when she grew up was “defined by the struggle to reconcile traditional Christian beliefs with newly emerging scientific concepts” (Emily Dickinson and the Church).

Receiving a Bible from her father when she was thirteen, Emily Dickinson and her family held religious observations in their home daily. She grew to have a thorough familiarity with scripture, which is displayed through her poems and letters. When she was a teenager there was a wave of revivals sweeping through the region, and her friends and family members made public declarations of their faith, one of the requirements for officially joining the church. Dickinson herself did not make such a declaration, and wrote in one of her letters, “”I feel that the world holds a predominant place in my affections. I do not feel that I could give up all for Christ, were I called to die” (Emily Dickinson and the Church).

Puritanism was a major influence on Dickinson’s religious beliefs. There were two systems of Puritanism, conformist and nonconformist (Monteiro). Dickinson’s family belonged to the latter group, which believed that the moral values expressed in Scripture was supreme, but that they were more than “grim idols cut in the stone” and that people should express their enthusiasm for their faith. But even this was still too strict for the young Emily Dickinson. Jennifer Gage asserts that while Dickinson craved the spiritual “nourishment” that Puritanism offered, she wholeheartedly rejected the restrictive and dogmatic rules that went along with it (Edison.) Scholar Barton St. Armand asserts that her beliefs and poetry were a form of “rebellion against the tyrannical Father-God of New England orthodoxy and a crisis of belief which took the form of an “Inner Civil War” (St. Armand 56).

One of the most poignant examples of Emily Dickinson’s disdain for traditional religion can be found in her poem “The Bible is an antique Volume” (1545). In this poem, she addresses the fact that the Bible was written thousands of years ago and questions the validity of its teachings on contemporary society. In the opening lines of the poem, Dickinson writes, “The Bible is an antique volume / Written by faded men / At the suggestion of Holy Spectres” (1-3). Loaded into these three lines are are Dickinson’s own opinions and skepticism of the Bible’s authority. In referring to the Bible as an “antique volume”, she not only is implying that the Scriptures are out-of-date, but also denigrates the prestige of the Judeo-Christian Bible by simply referring to it as a “volume.” For her, it is not a specific and holy book. It is just one of many books that are available. In the second line, Dickinson reminds all who would read her poetry that the Bible was in fact written by men, and “faded” men at that. Not only was this book written my mere humans, but humans who are not as whole or enlightened as they once were, again referencing the time that has passed between the books of the Bible being written and the time in which she lived. Through the next part of the poem, Dickinson offers up details about some of the “main characters” of the books of the Bible, notably Satan, Judas, and King David. She gives each of these characters a simple description, like referring to Judas Iscariot as a “defaulter.” In doing this, she paints these figures not in the superhero or super villain archetypes that they are typically cast as, but in more ordinary terms. Instead of their traditional roles, they become simple examples of sin and others facets of the human experience.

Another aspect of her beliefs continually expressed in her writing was what she believed would happen after one’s death, which can be found in her poem “I felt a funeral in my brain.” In this poem, the speaker is describing the sounds that she hears once she has passed away. In her mind, she can hear the sounds of her own funeral taking place. She hears the marching of the feet as they walk into the funeral, as well as the service taking place. After the funeral is finished, the speaker hear the creaking of her casket as she is being lifted and feels the dropping sensation as she is being lowered into the ground. In the last lines of the poem, Dickinson write that she “dropped down, and down / And hit a World, at every plunge / And Finished knowing – then” (18-20). The final line states that the speaker “finishes” knowing. She no longer has a consciousness and cannot sense her surroundings.

In Dickinson’s “I heard a Fly buzz – when I died (591)”, she once again chronicles the moments after death. In this poem, the speaker describes the atmosphere immediately following her death. While she is still lying on her death bed, surrounded by friends and family, she sees a light. Unexpectedly, a fly wanders into her line of vision, and she loses sight of the light. This poem illustrates the idea that, although the consciousness survives after death, it is only a temporary survival. This is contradictory to the vastly-accepted belief that the soul is in fact immortal and that one’s spirit immediately ascends into heaven upon death. Dickinson goes a step further in this poem, though, for not only is the speaker’s view of the “light” temporary, a simple, pesky creature such as a fly is able to come between the spirit of the departed and the afterlife.

This repeated image of the afterlife, when analyzed against the assumed beliefs of Christianity, seem to suggest that Emily Dickinson held views that were notably different than then usual idea that the soul immediate “wakes up” in Heaven after death. This would fall in line with her unconventional methods of practicing her beliefs, or the lack thereof (Monteiro).

There is another interpretation, however. One scholar, Mark Spencer, suggests that Emily Dickinson’s poetical interpretations of the afterlife are far more theologically correct than they appear. He asserts that, in the Revelation of John, the souls of the departed are described as only becoming eternal after the Second Coming of Christ. When a person dies, his or her spirit does not immediately ascend into heaven. It is only after Jesus’ return that the souls of the deceased will face their Last Judgement. So, the writing of Emily Dickinson “[makes] perfect sense if read from the perspective of a delayed final reconciliation of the soul with God” (Spencer).

This idea is well-represented in Dickinson’s poems about death. The sudden ending of consciousness in both “I felt a funeral in my brain” and “I heard a fly buzz when I died” can been seen as the period of waiting between death and ascension into heaven coming to an end. The spirit of the speaker does not disappear into nothingness, but instead completes its journey into the afterlife. The most supporting evidence of this is found in another of Emily Dickinson’s most famous poems, “Because I could not stop for death.” In this poem, death is personified as a suiter coming to call on the speaker.

In “Because I Could Not Stop for Death”, there are actually two entities in the carriage when Death stops for the speaker. These two are “Death” and “Immortality.” This, according to Spencer, is appropriate because the transition from humanly existence to spiritual eternity is a “two-step process.” Once death has occurred, the ascension into Heaven is “merely an expectation” (Spenser). This is further supported by the horses’ heads being described as pointing “toward Eternity.” The carriage ride does not end in “Eternity,” but it is headed that way. Spencer says, “the entire poem thus powerfully intimates that the speaker knows the new state she has entered is only a temporary one, a mere pause in the course of a carriage ride, but she does not presume to speculate on the nature of her ultimate destination, which she quietly and patiently awaits in a spirit of peaceful repose” (Spenser).

Dickinson’s poetry about death and the afterlife, or the lack thereof, is much more than her writing down what she believed. In her poetry lies the internal conflict that belief causes in all people. She moves from accepting doctrine to questioning the validity of the Bible. At times, the picture she paints of her spirituality almost resembles a nature-oriented paganism more than it does Protestant Christianity. In many of her poems, she personifies nature and the soul in the form of a female. This is reminiscent of the pagan traditions involving female goddesses and the worship of nature. In her poem “There came a Day – at Summer’s full”, there are many elements that can be interpreted as being pagan. The fullness of Summer references the summer solstice, or the longest day of the year. The solstices play an immensely important role in pagan religions. Also in this poem, certain capitalizations add something extra to the words. The first letter of the words “Sun” and “Flower” are capitalized, giving them their own personalities and implying importance. This adds more credence to the idea that she is expressing some form of paganism in her poems, as elements of nature are crucial in pagan religions. In the second half of the poem, she moves back to describing more traditional Christian images, such as the Lamb. With this change, this poem exemplifies the complexities of her spiritual life.

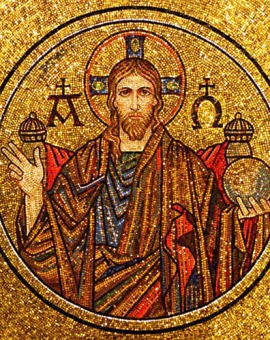

Standing alone, these descriptions of nature cannot be fully linked to paganism, but Dickinson makes more direct connections in her poetry. In particular is a short poem that she wrote to her friends, the Bowleses, for their eleventh wedding anniversary in 1859 (Habegger 381). In the second half of the poem, Dickinson writes, “Since I am of the Druid / And she is of the dew / I’ll deck tradition’s buttonhole / And send the rose to you” (5-8). Dickinson connects herself to “the Druid,” here. Interestingly, she seems to acquiesce to tradition at the very end, keeping with many of her other poems where she makes herself seem to be contrary to tradition, but still agrees, if reluctantly, to follow it.

Aside from references to paganism, there is even evidence that Emily Dickinson was interested in a movement that was taking the country by storm in the middle of the Nineteenth Century: Spiritualism. Spiritualism is the belief that the soul retains its consciousness and individual personality after death and that the spirit can and will communicate with the living through various methods. One method of communing with the dead is through spirit writing. For this to take place, people must open themselves up to control of the spirit and allow said spirit to take control of their hand while writing. In one letter to her friend Jane Humphrey, Dickinson makes references to her use of a “spirit pen” and how she allows a force to guide her writing. Although she does not plainly say that she engages in spirit writing, it does seem as though she is performing some form of the practice. In the 1860’s Dickinson wrote many letters to T. W. Higginson in which she says that she “psychically in tune with the spirit-guide of Nature” (St. Armand 345). There is, unfortunately, very little other evidence of her dabbling in Spiritualism, but given her attraction to beliefs associated more closely with mysticism than Christianity, it is not too difficult to come to the conclusion that she was interested in such a subject.

Even without a biography, much about Emily Dickinson’s life can be inferred from her poems. Aside from being a non-conformist in regards to religion, she also lived an extremely secluded life. Although educated and immensely intelligent, Emily Dickinson did not live a vivacious life. All humans experience some form of depression in their lives, whether temporary or a permanent condition. When a person is isolated from most other people, this depression and self-doubt becomes magnified. One of the starkest displays of the self-doubt and isolation that Emily Dickinson felt can be found in her poem “One need not be a Chamber- to be Haunted.” In the first stanza of the poem, Dickinson explains how the mind, which had is own halls and rooms, can be just as easily haunted as can a house, saying that the “corridors” of the mind actually surpass material places in size. Dickinson goes on to say, “Far safer, of a midnight meeting / External Ghost / Than it’s interior confronting / That cooler Host” (5-8). What lies inside her own mind is far more daunting that anything she could encounter in the real world. As someone who spent the majority of her life confined inside her house, Emily Dickinson had far more time than most alone with her own thoughts. Sometimes, her thoughts lead to fantastical verses about nature and the soul, but here, it leads her down a dark path in confronting her own self-doubt and uncertainty.

From reading Emily Dickinson’s poetry, one must eventually ask the question, “What does all of this mean?” Without careful analyzation of the verses she wrote, it is very easy to see someone whose mind must be a jumbled mess of ideas or a person who is very confused about what she actually believes. According to Gilbert Voigt, the theology crafted by Dickinson can actually be simplified into three “dogmas.” The first is her belief that human existence on the earth was essential and beautiful. Far from accepting the notion of “Original Sin,” she held no belief that humanity was inherently evil or that it needed to be cleansed in order to gain entrance into the next life. The second tenant of this theology is the beneficial qualities of suffering. Although she expressed incredulousness and even anger at God for the suffering of humanity, she still accepted a kind of reasoning that humans will be made better for it (Voigt 195). The third and final pillar, Voigt asserts, is her unfaltering belief in the immortality of the soul (Voigt 196). This seems contradictory to surface interpretations of her poetry involving death, such as “I heard a fly buzz- When I died.” When compared to the theory of Mark Spenser, however, this seems to make a great deal of sense. Spenser, who argues that Dickinson’s descriptions of a limited consciousness following death represents the “waiting period” between death and resurrection, would probably agree with this assertion that Dickinson did indeed firmly believe in the immortality of the human soul. Voigt goes on to perfectly describe Emily Dickinson’s theology as being

difficult to determine […] chiefly because of her strange contradictions and startling inconsistencies; her cries of doubt and her confessions of faith; her petulant indictments of God and her confiding appeals to him. One moment she is not sure there is another life; another time she is certain of it. On one occasion she accuses God of duplicity; on another, she expresses “perfect confidence in …. his promises.” Sometimes he seems a cruel enemy; again, an infinitely tender friend. In one mood she considers our universe impossible and cruel; in another, she finds human life ecstatically beautiful (Voigt 192-3).

This variety of spiritual representation presented in Dickinson’s poems does not show a changing opinion as much as they demonstrate the complexities that exist in all people. In some poems, she right bleakly about a temporary existence after death, while in others she writes verse almost like hymns seeming to keep with the traditionally accepted beliefs of the Christian Northeast. Then there are poems that seem to speak of nature and the spirits as in tune with each other, giving personalities to the Soul as well as elements of nature such as the sun or flowers.

A person’s spirituality is something that no scholar can never determine for sure. Though books and articles exist to chronicle a person’s birth and the other events in his or her life, but one can never know the content of another person’s heart. What scholars are able to see in the poetry of Emily Dickinson is what she wanted to believe. If Emily Dickinson’s poetry, the expression of her innermost thoughts and emotions, is any record, then scholars can know that her beliefs were extremely complex indeed. Through careful analyzation of her poetry, one can see the manifestations of Dickinson’s inner thoughts and conflicts about her life and her spirituality. Her doubts, hopes, and speculations about life, death, and everything that comes after can be found in the lines she penned.

Works Cited:

Crumbley, Paul. “Emily Dickinson’s Life.” Modern American Poetry. University of Illinois, n.d. Web. 21 Feb. 2016.

Dickinson, Emily. “Further in Summer than the birds.” The Poems of Emily Dickinson. Ed. R.W. Franklin. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London: The Belknap Press of Hardvard University Press, 1999. 388-389. Print.

Dickinson, Emily. “I felt a Funeral, in my Brain.” The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: The Traditions in English, Vol. 2. Ed. Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007. 1056-057. Print.

Dickinson, Emily. “I Heard a Fly Buss – When I Died.” The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: The Traditions in English, Vol. 2. Ed. Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar. New York: W.W. Norton, 2007. 1056-057. Print.

Dickinson, Emily. “Emily Dickinson – 1083 Poems.” Classic Poetry Series. Poem Hunter, 2012. Web. 09 Mar. 2016.

“Emily Dickinson and the Church.” Emily Dickinson Museum. Trustees of Amherst College, 2009. Web. 20 Feb. 2016.

Monteiro, George. “The One and Many Emily Dickinsons”. American Literary Realism, 1870-1910 7.2 (1974): 136–141. Web.

Spencer, Mark. “Emily Dickinson’s ‘Because I Could Not Stop for Death'” Explicator (2007): Heldref Publications. Web. 07 Mar. 2016.

St. Armand, Barton Levi. “Emily Dickinson and the Occult: The Rosicrucian Connection”. Prairie Schooner 51.4 (1977): 345–357. Web.

St. Armand, Barton Levi. “Paradise Deferred: The Image of Heaven in the Work of Emily Dickinson and Elizabeth Stuart Phelps”. American Quarterly 29.1 (1977): 55–78. Web.

Voigt, Gilbert P. “The Inner Life of Emily Dickinson”. College English 3.2 (1941): 192–196. Web.